In this city of light, it is the shadows that remember—and the bells that awaken the soul.

The Dream shifted its kaleidoscopic shapes, and Paris returned—shimmering and alive, a familiar sensory heaven drawn from memory and longing. After Berlin’s wide, raw spaces, it pressed close—intimate, dense, steeped in centuries.

The small flat waited on the fifth floor of 18 rue des Écouffes, a narrow artery in Le Marais, once the heart of the city's Jewish quarter. From a large window in the small apartment, light poured in and an intimate view of the city shone. The name—Écouffes—was said to once evoke scavenger birds circling medieval rooftops. The birds are long gone, but their vanished wings still seem to move through the air above the rooftops of the present day.

Each morning, stepping onto the worn cobblestones, the air lifted with the scent of challah and fresh croissants. Sometimes lovers fastened padlocks to the railings of the nearby Pont Neuf Bridge and tossed the keys into the flowing Seine, or wandered hand in hand beneath wrought-iron balconies, while café conversations spilled into the streets like music.

A few paces east, Place des Vosges unfolded in perfect symmetry—a garden cradled by arcades and chestnut trees, where light pooled gently and time loosened its hold. Once the royal square of Paris, it felt almost monastic in its stillness, though framed by noble façades of red brick and stone. The clipped lawns, gravel paths, and weathered fountains lent it the air of a living painting—balanced, composed, quietly breathing. Around the corner, on Rue des Rosiers, the clatter and cheer of falafel shops blended with the quiet reverence of hidden synagogues.

A quiet summons rose—an urge to return to Père Lachaise, the largest cemetery in Paris. Though familiar from a past visit, the call felt deeper this time, more personal. Perhaps it was because my daughter Naomi, who had died nine years earlier, journeyed with me still—a quiet companion in The Dream. Across cities and continents, she walked beside me—not in sorrow, but as a loving, joyful presence woven into the fabric of being. Behind every person photographed, she stood smiling, lending courage and grace to the act of seeing, while allowing familiarity and spontaneity.

The quiet lanes of Père Lachaise opened like a forgotten chapter. Famous names drew the crowds—Jim Morrison, Théodore Géricault, Chopin, Oscar Wilde, Balzac, Colette—but something older called more strongly. Ancient mausoleums stood in various states of collapse, their doors sealed or ajar, interiors dim and half-surrendered to time. Many had been left untended, as though the families who once mourned there had vanished too. Light filtered through stained glass and fractured panes, casting colored shadows on old urns, dead flowers, and cobwebs spun thick across corners. Inscriptions chilled with centuries of dates. Time made visible—its beauty, its stillness, its quiet unraveling—held me still.

Photographs came in rapid succession, each one offered by instinct. The world narrowed. Time loosened its grip and gave way. Somewhere, a distant bell rang, signaling the hour—but sound dissolved in the hush of focus. Only much later did the stillness around reveal itself: the gates had closed. A search for an exit proved fruitless, until a low wall presented the only escape. I climbed and landed in a quiet street beyond, pulse quickened and laughter rising—grateful, strangely, for the odd episode, and glad not to be spending the night with the dead. Of all the places to be locked in, at least the company had been unforgettable.

From my window, the city’s allure reached me: cathedral bells pealing through the late-summer air, filling my bones with a familiar, wordless joy. Gaiety shimmered everywhere, as if the richness of Parisian life demanded an overflow of spirit. The streets offered endless invitations—fine clothing shops, art galleries, boulangeries, and tiny, glittering storefronts selling everything from bio beauty aids to exotic jams. In just a short walk along Rue de Rivoli, the pastiche dazzled: music, flowers, currency exchanges, sushi counters, wine merchants, toyshops, optical stores, patisseries. A dream within a dream.

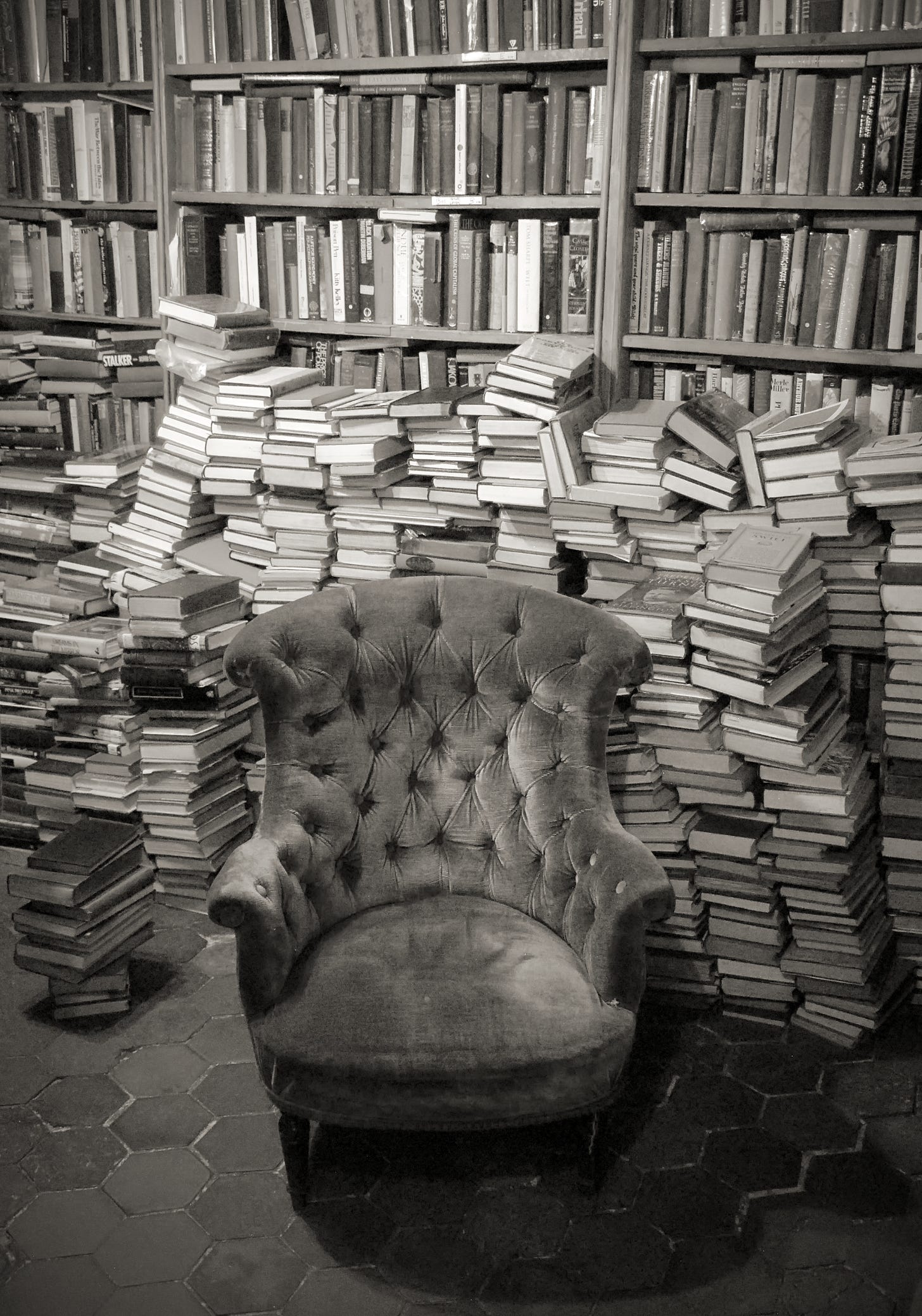

Along the Seine near Notre-Dame, a weathered green sign marked the entrance to Shakespeare & Co.—a legendary bookstore nestled like a secret between stone and water. The narrow three story building itself leaned slightly, like most things in Paris that have been loved too long and too hard. The green façade faced the river, defiant and weary, like it had seen too many revolutions—literary and otherwise. Inside, the air carried the scent of book-dust, old paper, and damp wood. The floorboards moaned underfoot. Shelves climbed to the ceiling, and the walls felt crowded—like the mind of someone who never throws anything away.

Tourists moved through in a kind of reverent hush, fingers trailing along spines as if touching relics. English filled the space, wall to wall—books stacked on stairways, tucked into nooks, filling the silence with invisible voices. A cat stretched beneath a radiator. On the upper floor, a piano sat quiet beside a window overlooking the Seine. Nearby sat an old typewriter in stillness.

For decades, the store was run by an American expatriate, George Whitman, who believed books could build a kind of sanctuary. He welcomed aspiring writers to sleep among the shelves—drifters and dreamers he called “Tumbleweeds.” Like the windblown plant, they had no roots, drifting in from all corners of the world, seeking something—freedom, inspiration, or refuge. In exchange for a place to sleep, they helped with daily tasks: shelving books, sweeping floors, brewing tea. But more than chores, there were three requests:

• Read a book a day.

• Write a one-page autobiography for the store’s archives.

• Help out for a couple of hours daily.

Thousands passed through. Some stayed days, others weeks, a few even months. Many went on to publish books or live artistic lives elsewhere, always carrying that strange, luminous memory: sleeping in a bookstore, the scent of musty pages in the air, the bells of Notre-Dame tolling across the river.

Wandering the narrow aisles, a quiet kinship stirred—echoes of those who had come before, pausing here in their search for meaning or refuge. It was easy to imagine staying on: shelving books, reading until the light changed, writing in the hush before dawn. For a moment, I felt part of that lineage—a Tumbleweed in Paris.

Eventually, the path led back outside, where the spires of Notre-Dame pierced the sky. High above, gargoyles crouched—stone sentinels gazing outward, watching over the city. In medieval imagination, they guarded the sacred by embodying the grotesque, frightening away evil with fearsome faces. Some believed they gave refuge to restless spirits—creatures forged from anguish and chiseled into permanence.

There was something to admire in them. They bore the weight of the darkness, making space for the light to dwell. That had once been the struggle for me—wrestling with the hidden places, denying the shadows within. Exhausted, a mental break occurred. Healing had been painfully slow. Until everything was brought into the light to be acknowledged and blessed, the suffering remained. For release and freedom, love had to be total, not partial. Without self castigation or denial. The Dream contains all.

The gargoyles, with their gnarled mouths and weathered eyes, did not console or accuse. They simply endured. Keepers of shadow, bearers of truth. Witnesses from the heights of centuries, unmoved and unspeaking. No wonder I loved seeing them.

Though Paris came dear—the cost of daily life higher than anywhere I’d been yet—the city's energy made it easy to accept. I was working well. A few paintings took shape, and I shot hundreds of street photographs. That’s how it was—days moved fast, filled with images.

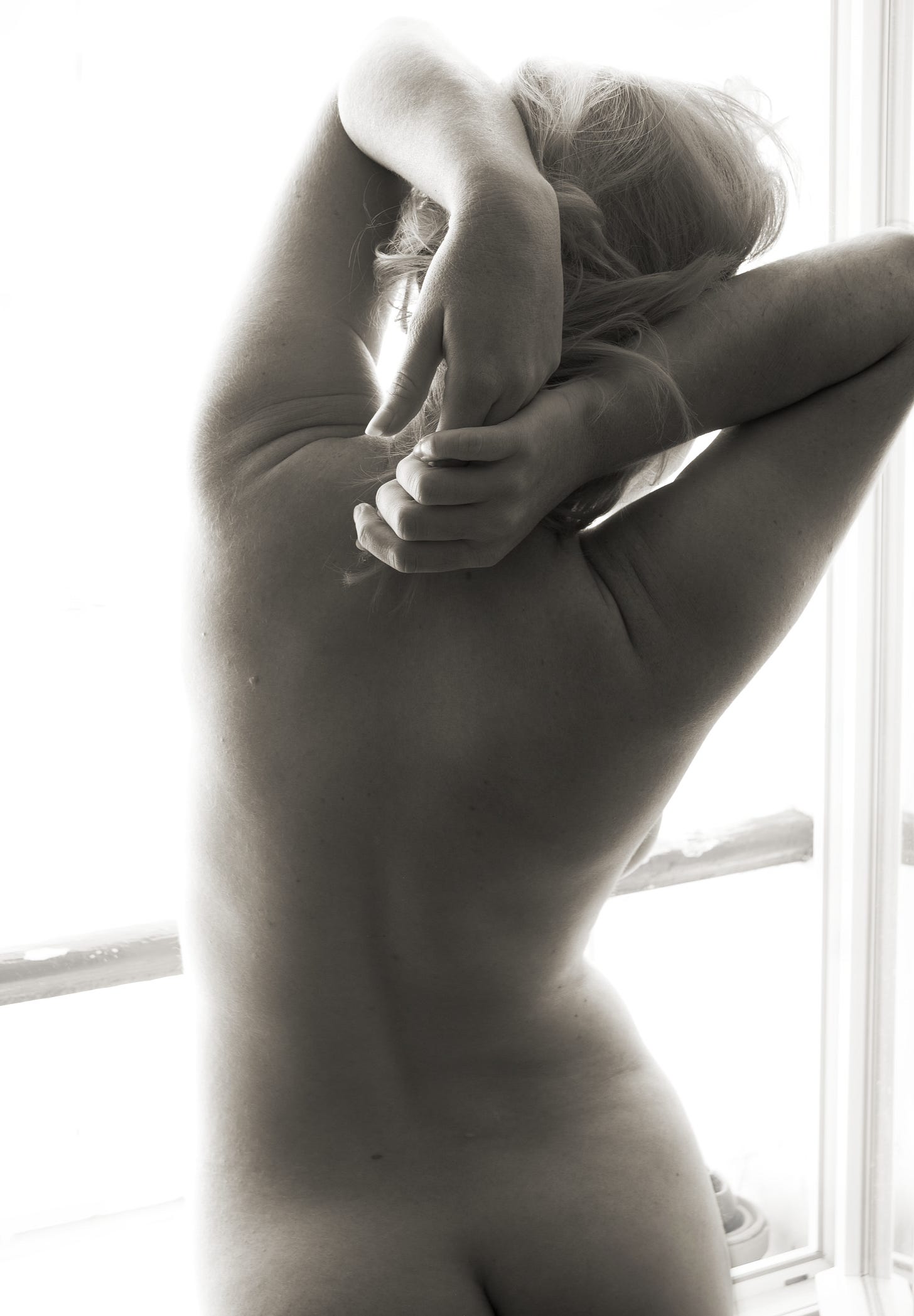

Ange came via Craigslist. She’d posted as an artist’s model and arrived at my flat one afternoon. I didn’t paint her—only photographed. A visiting American, twenty-seven, with bleached blonde hair, full-bodied, Rubenesque. She explained that she was a lawyer, a forensic psychologist, a painter, a model, and spoke several languages. "When I go to work, I have to pass through three locked secured areas."

I suggested she take inspiration from Masaccio’s Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, (1424–27). She knew the painting and instinctively adjusted her body, striking the pose with startling precision. In the original, Adam stands nude and muscular, bowed in shame, covering his face as he leaves Eden. Eve, also nude, shields her breasts and groin, her face lifted in a raw, silent cry of grief. Tears streamed down Ange’s cheeks—real ones—as she entered the moment fully. We hit it off.

A few days later, we met again at the Rodin Museum. Outside, sitting on a bench in the garden among sculptures under spreading trees, her hand, the same hand I had studied and photographed, rested on her bare knee. A cigarette dangled from her fingers, smoke rising slowly in the still air. Before parting, we promised to stay in touch.

The currents of the Dream drew me upward to Montmartre, the old hill of artists and dreamers. From the steps of the Sacré-Cœur, the city unfurled below in a mist of rooftops and ancient light. I wandered the cobbled lanes where painters still set up their easels near the church, brushstrokes capturing fleeting impressions as tourists and locals drifted past. The spirit of Toulouse-Lautrec and the bohemian age lingered faintly, especially near the Moulin Rouge, where the red windmill spun its promise of spectacle.

Above ground, Paris shimmered with history; below, the Métro pulsed with another kind of life. Camera in hand, I descended into its labyrinth, drawn to the raw, kinetic poetry of bodies in motion—strangers brushing past illuminated advertisements, their faces briefly lit like passing apparitions before vanishing into the endless rhythm of the underground. The flux of light and motion sparked creativity, emboldening the camera shutter to trigger often. Later, in my apartment I could sort through them, keeping the best. On the streets or below, inspiration arrived non stop.

Museums demanded attention, as they held many of the masterpieces every true artist carries in memory. The Louvre—world’s most visited and often deemed the most prestigious—consumed an entire day, and still, it was not enough. So many of the works once studied in classrooms or seen in well-worn books now stood before the eyes, vivid and breathing. Though its dominant tone leaned academic and classical, the place spoke of something grander: a museum of civilizations.

By day’s end, fatigue set in—legs aching, back sore from endless walking and standing on marble floors—but a quiet thrill remained, the inner hum of having reached an art Mecca and moved through it inspired, almost prayerful. To stand before the Mona Lisa, then slowly orbit Michelangelo’s Dying Slave—one of the Louvre’s Renaissance treasures—and feel in its delicate torsion a subtle erotic pulse: a young man in his prime, nude, arrested in the elegant throes of death.

The Pompidou, the Musée d'Orsay—with its breathtaking Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, Monet, Degas, Van Gogh—the Musée d’Art Moderne, the Picasso and Rodin Museums, each called in turn, and were answered. Versailles, with its famous palace and gardens, though urged by dear Sabine as unmissable, remained a promise unkept. The days of late summer were golden, the tourist tide receding, and the sense of discovery felt at once vast and evanescent.

Paris, with all its nuance and layering, revealed itself as a grand illuminated manuscript—pages and passages impossible to absorb entirely in the space of two short weeks.

As in every great city, so much would remain unseen. But what had been gathered was more than enough: the view from my window over red-tiled rooftops, the hush inside the Musée Picasso, the chance meeting with Ange, the treasures of art—masterpieces once studied in books now seen with my own eyes—and the life of the streets, with all its myriads of fleeting wonders. A fullness lingered. On my last morning, dragging my suitcases over the cobblestones toward the train, my heart quickened with a tinge of remorse at the thought of leaving. Paris had given richly, and stepping away felt like departing from a dream not quite finished.

The river carried me onward—toward Rome, another fabled city waiting at the far bend of time. But Paris had held me close—and cradled me still. Even in parting, something remained: a trace in the blood, a music under the skin.